One of the special events of the 2013 Texas Architects Convention in Fort Worth was a tour of three small chapels led by James Nader, FAIA. The tour was presented by the Texas Office of Partners for Sacred Places, a national non-profit whose purpose is the preservation of historic church facilities. What is unique about their mission is that they treat preservation as one aspect of ensuring the vitality of the historic church community who calls the building home. They are the "only national advocate for the sound stewardship and active community use of America’s older religious properties."

One of the special events of the 2013 Texas Architects Convention in Fort Worth was a tour of three small chapels led by James Nader, FAIA. The tour was presented by the Texas Office of Partners for Sacred Places, a national non-profit whose purpose is the preservation of historic church facilities. What is unique about their mission is that they treat preservation as one aspect of ensuring the vitality of the historic church community who calls the building home. They are the "only national advocate for the sound stewardship and active community use of America’s older religious properties."

The Texas Office also just announced the launch of the Texas Sacred Places Project website with the goal of creating an inventory of purpose-built religious buildings designed for worship and more than 50 years old. This looks like a wonderful project and I look forward to exploring it and contributing.

The three chapels on the Fort Worth Sacred Places Tour were the Dorothea Children's Chapel at St John Episcopal, the Marty Leonard Community Chapel at Lena Pope Home, and the Oakwood Memorial Chapel at Oakwood Cemetery. Walking around downtown during the convention I also visited First Christian Church and St Patrick Cathedral, so those two are included below as well. (All of the published photos from the trip are in this Flickr collection. I still need to add the two O'Neil Ford churches in Denton and the non-church projects as well.)

Photos and some thoughts on each of the churches follow bellow.

Dorothea Children's Chapel at St John Episcopal

The first stop on the tour was a "diminutive" English Gothic chapel built in 1966. Architect and church member Joseph J Paterson proportioned and detailed every aspect of this chapel for use by children.

Note the use of "reject" clinker to accent the rustic character. The exaggerated thickness of the walls contribute to the somber weight of the building. Above the door of the chapel, inverse corbeling lightens the wall on the interior as it rises to the small rose window above.

As an adult, the chapel feels like trying to play a 3/4 size instrument. The windows, pews, and other furnishings feature animal figures and depictions of the childhood of Jesus.

The Dorothea Children's Chapel was an addition to the main church which was also designed by Paterson and built in 1952. Paterson modeled the church on his studies of Gothic parish churches found on his travels in England.

A few characteristically Anglican features show this influence, most notably the full chancel with quire. The chancel is missing a rood screen, but the lady chapel terminating the left aisle does have one. A metal rood screen also separates the Children's Chapel from its narthex (above).

The squat central tower is another common feature of Victorian Gothic churches.

View the complete photo set of The Dorothea Children's Chapel and St John Episcopal on flickr.

Marty Leonard Community Chapel at Lena Pope Home

The centerpiece of the tour was an interfaith chapel at the Lena Pope Home, which opened in 1930 as a home for orphans. The Home still housed disadvantaged children at the time of the chapel's construction (1990), but its mission has since changed to focus on enabling families to stay together through counseling, a charter school, and other educational programs. The chapel has remained in constant use by the Home and the community it supports (plus lots of weddings).

The purpose of the chapel was similar to the Austin State Supported Living Center Chapel previously featured on Locus Iste.

A plaque on the floor of the narthex states the Chapel's Mission Statement:

The Marty Leonard Community Chapel provides a serene setting where the youth of Lena Pope Home can give and receive acceptance and forgiveness, develop character, understand the unexplainable, accept the unacceptable, forgive the unforgivable, develop and refine a moral values system, and seek peace and a new beginning.

The Chapel provides a peaceful place where the youth can let down their walls and where they can surrender and relinquish control of their lives to a higher power that will not abandon them, will not abuse them, will not judge them, but will love them no matter what, and forever.

This interfaith chapel provides an uplifting environment that inspires people to think their highest and best thoughts. It is a place for worship, inspiration, prayer, guidance, celebration, joy, meditation, hope, relaxation, research, education, music, and spiritual enrichment.

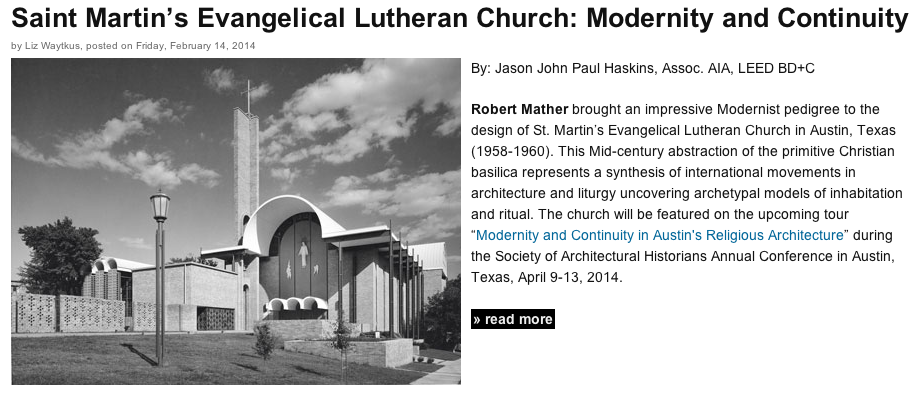

Our guide for the tour was Marty Leonard, the chapel's namesake. She wanted to build a chapel for the Lena Pope Home, and her friends gave it to her as a birthday present. Leonard hired the architect E Fay Jones, most well known for Thorncrown Chapel near Eureka Springs, Arkansas. Jones was an apprentice of Frank Llyod Wright, and his influence shows clearly in both of these chapels, especially in moments like these:

Which is not to say that Jones was not a designer in his own right. He developed a unique interpretation endemic to the Ozark forests that was an analog to Wright's prairie architecture rooted in the midwest or his desert architecture based out of Taliesen west. Moreover, Fay Jones was an extremely well regarded professional, as a Fellow of the AIA and recipient of the AIA Gold Medal in 1990, an well as an influential educator. The University of Arkansas named their School of Architecture in his honor after his death.

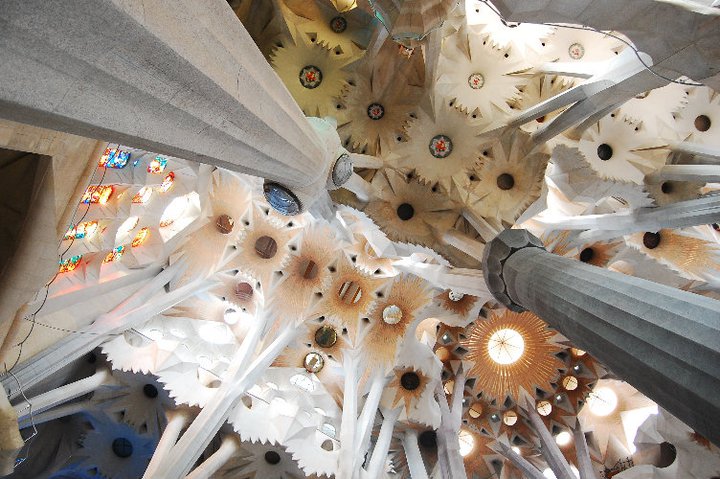

The timber filigree structure was the chapel's distinguishing characteristic and one that was evident from photographs. And it was indeed impressive, but in person the spatial sequence was the most interesting aspect as it moved from the dramatically vertical façade, through a low narthex, and into an open worship space. Compared to the initial impression of strong verticality add the linearity of the tectonics (along with the Thorncrown precedent), the broad central character of the nave was unexpected.

The entry space with service facilities is unusual among Fay Jones chapels; he typically preferred to use outbuildings for restrooms and other program requirements in order to maintain the architectural purity of the chapel itself. But the Leonard Chapel includes a full lower floor with a meeting room, office, kitchen, and restrooms.

While Thorncrown may be the more pristine formal Architectural experience, the missional program of this chapel and the spatial complexity it required results in a more complete architectural work.

View the complete photo set of the Marty Leonard Community Chapel on flickr.

Oakwood Memorial Chapel at Oakwood Cemetery

Our last stop on the tour was a small cemetery chapel in desperate need of preservation. Oakwood Cemetery was described as the burial place of the "notable and notorious" of Fort Worth.

A group of women raised the funds to build the chapel in 1912. Architects Marion Waller and E Stanely Field provided the design. The timber roof structure in the small chapel was exquisite.

We were also able to visit the basement of the chapel which at one time housed one of the first mechanical coffin lifts.

View the complete photoset of Oakwood Memorial Chapel on flickr.

The next two churches were not part of the tour, but visited during some free time during the convention.

First Christian Church

Walking back from breakfast Saturday morning, I saw a dome across a parking lot that merited investigation.

The building turned out to be First Christian Church, the 1914 neoclassical home of the oldest continually operating congregation in Fort Worth. The architects were E.W. Van Slyke and Clyde Woodruff.

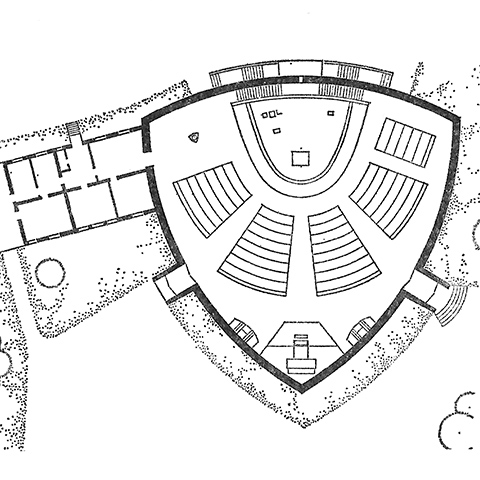

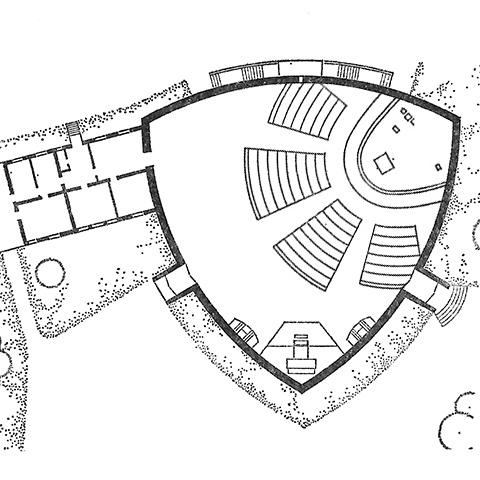

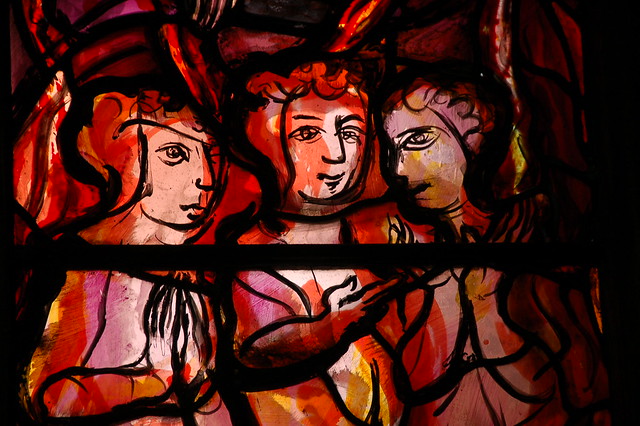

The interior revealed a quarter-radius auditorium about a corner sanctuary. This was an unusual arrangement, given the asymmetry of the choir loft over the baptistry, the interior stained glass opposite, and other irregularities.

The dominant feature of the main worship space was a large domed skylight of stained glass centered over the nave.

View the complete photo set of First Christian Church, Fort Worth on flickr.

St Patrick Cathedral

St Patrick Church started out as the first parish church in Fort Worth in 1888. It was later elevated to co-cathedral of the Diocese of Dallas-Fort Worth in 1953. It has served as the Cathedral of the Diocese of Fort Worth since its establishment in 1869.

Architecturally, the structure was the Gothic Revival typical of large Catholic churches in 19th century Texas. But the ornamentation and especially the sanctuary were given a more Renaissance treatment.

The result is the kind of indiscriminate traditionalism that feeds sentimentality. All three altar pieces are topped with broken round pediments, emblems of Renaissance absurdism.

View the complete photo set of St Patrick, Fort Worth on flickr.

The hagiography of St Francis, whose

The hagiography of St Francis, whose