Goodhue's Tomb: Nihil Tetiget Quod Non Ornavit

/The tomb of architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1869–1924) rests in the Episcopal Church of the Intercession in the far northwest of Manhattan. It is a fitting location as he reportedly considered the Church of the Intercession to be his most beloved work (though perhaps because he did not live to see St Bartholomew completed in 1930).

I have been working on this study off and on for more than a year after I visited the Church of the Intercession during a trip to New York City in the summer of 2014. My photos from that trip have been in a sort of development limbo partly because I seem to have unintentionally adopted a LIFO queue for my churchcrawling photos and partly because the main feature of the trip, Jean Labatut's Stuart Country Day School, is an intimidating prospect in terms of the volume of photographs taken and the quality of research it deserves.

Aside from the excursion to Princeton, that trip turned out to be all about Goodhue, including a beautiful celebration the feast of St Dominic at the Dominican church of St Vincent Ferrer. The Church of the Intercession was not originally on my itinerary, given how far north it is and the fact that my wife and I visited the Cloisters (which is further north) but only had time for the museum that evening. But when I found out about the tomb, I rearranged my itinerary (which was pretty loose on this particular trip anyway) and made may way back up the 1 to 157th.

The tomb itself is built into the wall of the shallow north transept.

I'm not sure if it is more surprising to come across this monument or that it is so rare that architects have such dramatic monuments. The only other architect's tomb that comes to mind is that of Sir John Soanne, a mysterious composition that may have inspired Sir Giles Gilbert Scott's iconic phone box design. In this case, the large, elaborate tomb reflects Goodhue's friends, their love and admiration for him, as well, I think, as a certain intellectual jocularity they shared.

His biographies and the surviving personal accounts all portray Goodhue as overflowing with joyfulness, generosity, kindness, romanticism, and appreciation of beauty. Michael Anderson, the biographer of Goodhue protégé James Perry Wilson, described Cram and Goodhue as part of Boston's "bohemian intelligentsia where all manner of creativity, flamboyance, and eccentricity, as well as the serious study of art and architecture, was the norm." For a good sense of Goodhue's personality and life in his New York studio, I highly recommend reading this chapter from Michael Anderson. Anderson also quotes this description of Goodhue's personality from Ralph Adams Cram: "Blond, slender, debonair, with a school-girl complexion and a native grace of carriage, he presented a personality made up of joy of life, fantastic humor, whimsical fads and fancies, blended with...an incomparable sense of beauty, an abounding friendliness...". He seemed to have had the ideal personality to lead a studio of creative professionals: encouraging and inspiring, demanding but liberating.

In this light, the grandeur of the monument makes sense. And it is this that inspired its creation. The lower portion of the monument reads (in a Gothic textura majuscule):

BERTRAM GROSVENOR GOODHUE MDCCCLXIX MCMXXIV THIS TOMB IS A TOKEN OF THE AFFECTION OF HIS FRIENDS HIS GREAT ARCHITECTURAL CREATIONS THAT BEAUTIFY THE LAND AND ENRICH CIVILIZATION ARE HIS MONUMENTS

The stone-carving is the work of sculptor Lee Lawrie (1877-1963), a close friend who worked with Goodhue on nearly every one of his public commissions. Lawrie's most well-known work apart from his collaborations with Goodhue is the Atlas and reliefs for the Rockefeller Center. For more on this master of Art Deco sculpture, see this feature on the Louisville Art Deco website or the more detailed biographical information and galleries on leelawrie.com, both the work of Gregory P Hamm.

Lawrie also carved likenesses of Goodhue for a capital the West Point Chapel (later removed):

and for a transept portal at the University of Chicago Rockefeller Chapel where he represents the visual arts opposite J.S. Bach representing the musical / performing arts:

That he would be depicted as equal to such esteemed company reflects the high degree to which he was respected in his lifetime.

So there are in fact a number of monuments to Goodhue. Another was proposed for the California Institute of Technology campus and a neighborhood group in Lincoln, Nebraska is currently working on erecting a monument in his honor.

My alma mater honors him on the West façade of UT's Goldsmith Hall (School of Architecture) with the likes of Vitruvius, Ictinus, and Palladio, the only four names so venerated.

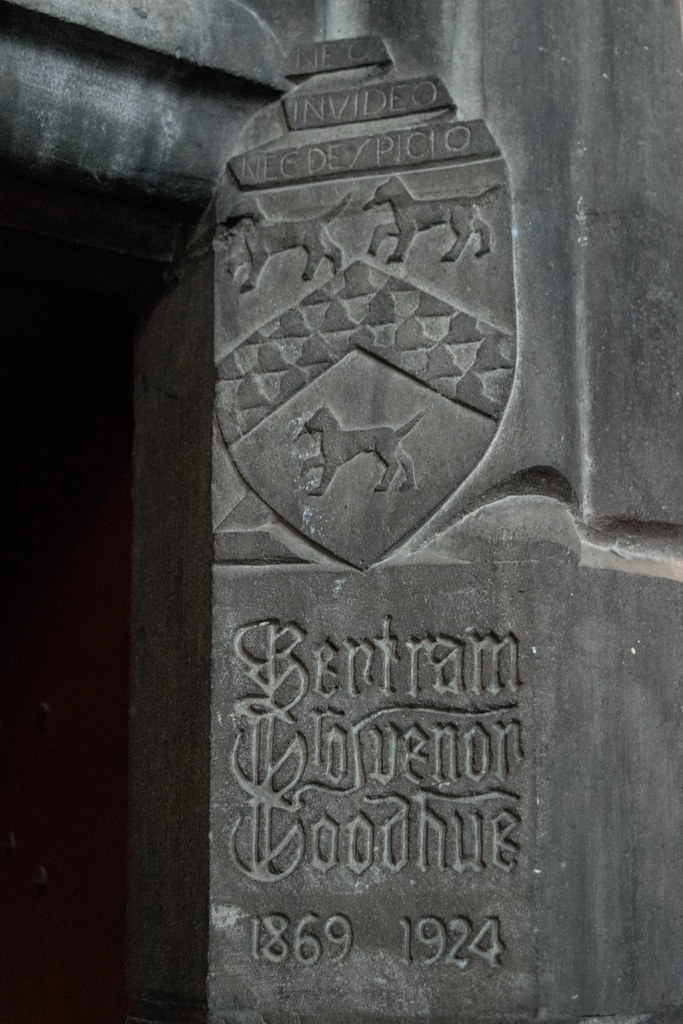

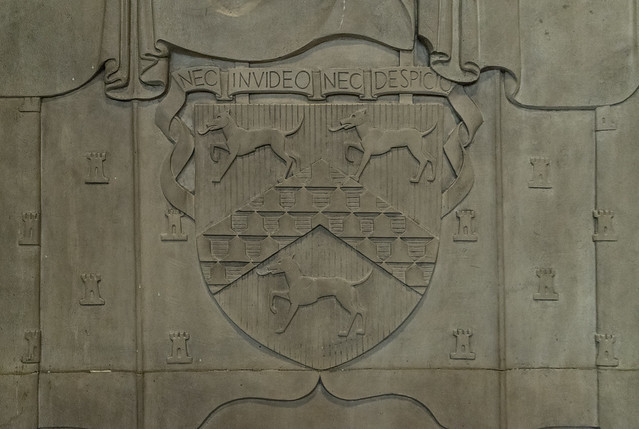

But the tomb in the Church of the Intercession is a most fitting tribute. The centerpiece of the monument is a life-size recumbent effigy of Goodhue in high relief after the manner of those preserved in medieval English country churches. At his feet rests a pegasus as a symbol of creativity (wisdom + inspiration). The figure's shroud drapes over the side on the monument to reveal the interior surface bearing a pattern of towers and emblazoned with the Goodhue family coat of arms.

The family arms (Gules a chevron vair between three talbot passant argent, if I have blazoned that correctly) are also carved into the mantel of Goodhue's architectural offices (which have survived nearly intact but are now threatened with demolition) and beneath his image in the Rockefeller Chapel.

The family arms also include the motto nec invideo nec despicio ("I neither envy nor despise") on a scroll chief.

But the truly dominant feature of the tomb—and the one that most reflects Goodhue's personality—is the upper frieze comprising a series of his architectural works beneath the epitaph nihil tetiget quod non ornavit (a phrase typically rendered "he touched nothing that he did not adorn").

I highly recommend clicking through to view these images of the frieze full size to see the detail. The photos are a little grainy since they were photographed hand-held in low light, but the quality is enough to zoom in for specificity.

The epitaph nihil tetiget quod non ornavit originates from that of Dr Samuel Johnson on Irish poet Oliver Goldsmith. The text of the monument to Goldsmith in the Poet's Corner in Westminster Abbey reads (according to the Appendix to The Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B.: With a Life and Notes, Volume 4 (1835), p. 325; see also Boswell’s Life of Johnson. Illustrated. Vol. III.):

Nullum fere scribendi fenus non tetigit,

Nullum quod tetigit non ornavit;

Sive risus essent movendi,

Sive lachrymæ,

Affectum potens, at lenis dominator :

Ingenio sublimis, vividus, versatilis.

Oratione grandis, nitidus, venustus.

In reference to this inscription, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley (1815–1881) In his Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey noted that "one expression, at least, has passed from it into the proverbial Latin of mankind—Nihil tetigit quod non ornavit." This form of the quote, which seems not to have originated with Stanley, was repeated elsewhere. A footnote gives the epitaph as "Nullum scribendi genus guod tetigit non ornavit," which also differs from the actual inscription and has added to the confusion around the phrase (as documented in a 1917 issue of The American Journal of Philology 38, No. 4 (1917), pp. 460-462.). Neither of the forms given in Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey matches either the actual inscription on the Goldsmith monument or that on the Goodhue, which adds the wrinkle of the apparent misspelling of tetiget for tetigit. But the intent is clear: to praise Goodhue's creation of beauty and link him with most highly esteemed literary and artistic figures.

It was fascinating to see these buildings rendered in stone, four of which I visited on the same trip. But I wanted to know what all of them were. I was able to find online a few descriptions of the buildings depicted in the frieze, but none of them were accurate or complete; a few descriptions list Rice University and the Cathedral of St John the Divine. Goodhue worked (with Ralph Adams Cram) on both of these projects, but after positively identifying every element of the frieze, neither of these works were included. They were likely misidentifications of the NAS or Caltech building and the Baltimore Cathedral respectively.

The Baltimore Cathedral (the second building from the left) gives an indication of the challenge of identifying the works but also the clues included that aid in identification. And it provides the key to understanding the motivation and spirit behind this work. Goodhue's design for the Episcopal Cathedral of the Incarnation in Baltimore was never built, so looking only to the built versions of his buildings would not be sufficient to identify all of the works on the tomb. But the frieze includes the episcopal arms of the Diocese of Baltimore to aid in identification, and the version carved here precisely matches one of Goodhue's own renderings of the design.

The Cram & Goodhue designs for Rice do resemble a combination of the Caltech and NAS depicted on the tomb, but the heraldic shields and the specific drawings evidently referenced by Lawrie make their identification clear. At the end of this post there is a comparative image for each of the works featured with either the corresponding drawing (when identified) or a photo of the building.

After a few trips to the library, some interlibrary loans, and many fruitless google searches attempting to identify all of the buildings on the frieze, it became clear that some of the difficulty came from the fact that even some of the more easily identifiable buildings did not match their final built designs and that others were in fact unbuilt designs or even imagined scenes.

Since many of the sculpted representations match the renderings precisely, we can conclude that Lawrie carved the tomb predominantly from drawings and sketches. This makes sense as it would reflect the reference material he had on hand to work from. But it also speaks to Goodhue's status as a skilled draughtsman and artist in addition to architect and to the importance of scenographic drawing and in his architecture. It also pays homage to the architect's sense of humor and playfulness reflected in his own composite follies, such as the 1914 fantasy below that also includes the Baltimore Cathedral, West Point Chapel, Panama-California Exhibition, Church of the Intercession, St Thomas, a number of residential works, and some bonus architectural features to tie them all together.

This scan comes from a monograph entitled Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue: Architect and Master of Many Arts published in 1925 by the Press of the American Institute of Architects. (It is an expansion of an earlier Book of Architectural and Decorative Drawings published in 1914). In addition to orthogonal drawings, renderings, and photographs of his architectural works, the book featured Goodhue's typographic work and bookplate designs. Also included were a number of "sketchbook scraps" and fantasies.

Goodhue drew many such compositions, including a depiction of Xanadu, several imagined buildings, and at least two entire constructed towns (the Germanic Traumburg and the Italian hill town of Monteventoso) complete with narrative histories based on places he experienced in his travels. There is an excellent and well illustrated discussion of these towns and his drawings in general on the blog Beyond Architectural Illustration.

An earlier sketch in the Lawrie archives at the Library of Congress shows the of buildings inset behind the effigy. This concept more closely resembles Goodhue's own composite follies. But the final design shares the use of vertical landscape as a unifying technique. And as will become clear, the depiction of the individual buildings derives heavily from Goodhue's drawings.

A heraldic escutcheon accompanies most of the buildings. These shields use either the existing arms of the client or construct new ones using imagery traditionally related to the identity of the client organization. Using these elements and the drawings available, I was able to positively identify each of the buildings on the frieze. Here is for each a brief synopsis and an explanation of the imagery that accompanies it.

Cadet Chapel, US Military Academy West Point

The full rendering of the Cadet Chapel perched atop its cliff is one of Goodhue's finest pencil drawings. The romanticism of the drawing comes in part from the highly picturesque site of the building and the romanticism of the architectural response to that site. Goodhue revisited this image of the towering edifice integrated with a vertical landscape. Perhaps the most dramatic version is in the Lady Chapel of the proposed Baltimore Cathedral (next in the order) which spanned a road before projecting out over the bluff above the city.

Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson won a competition in 1906 to redesign the campus and to design several prominent buildings, of which the chapel was the centerpiece.

A shield with the sword and helmet of Athena, the suitably violent escutcheon from the US Military Academy's coat of arms, accompany this first building.

Episcopal Cathedral of the Incarnation, Baltimore, MD (unbuilt)

The second work on the tomb is the Episcopal Cathedral of the Incarnation Design work began in 1913, making it one of the first major commissions of Goodhue's individual practice. He produced at least two elaborate schemes for a large diocesan complex, but post-war financing issues, Goodhue's death, and the Great Depression all contributed to the need to reduce the scale of the architectural vision. For more on the history of the church as built, there is some information on the cathedral website.

The coat of arms of the Diocese of Baltimore are above the building.

National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC

Located on the far northwest end of the mall in Washington, D.C., the Academy's building was dedicated in 1924, the year of Goodhue's death. For more information on the history of this building, visit this excellent resource on the NAS website.

In this case, the building as built matches the domed version carved into the tomb rather than the published drawing. The building features many sculptures by Lee Lawrie and mosaics by common Goodhue collaborator Hildreth Mière cover the interior of the dome.

The escutcheon accompanying this building bears the initials NAS and the head of a Lynx. I have not been able to confirm if the National Academy of Sciences has ever used this emblem, but it is undoubtedly an homage to the Accademia dei Lincei, a scientific society formed in Italy in 1603 and named for the Lynx. The Lincean Academy later became the national academy of Italy when re-founded in the 19th century, and is something of a prototype of such national academies. Lawrie's copper parapet (or chéneau) feature alternating owls and lynxes "symbolizing wisdom and alert observation, respectively."

California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA

Goodhue's involvment with the design of the campus of the California Institute of Technology began in 1917.

The shield identifying the Caltech campus is a palm tree with the initials "C" and "T" on either side. The palm tree has been used by the University, but I have not been able to confirm if this particular emblem has been an official

Church of the Intercession, Manhattan, NY

As mentioned, the Church of the Intercession is the location of Goodhue's Tomb. The façade composition is a common feature of Goodhue's churches: strong vertical elements framing a window and a pronounced lower portal element. Compare the designs for West Point Chapel and St Vincent Ferrer also on this frieze with St Thomas which has a more typical single-tower Gothic Revival design with a more direct High French Gothic influence.

Convocation Tower, New York City (unbuilt)

The Convocation Tower was a proposal for a skyscraper for Madison Square. The project was never built, but would have made for an enriching contribution to the New York skyline in an exciting era of tall building design.

The rendering of the tower shown here does not exactly match the carving (it appears to be a view rotated 90º). The rendering is by Hugh Ferriss—the great Art Deco Piranesi—in his characteristic dramaticly-lit and heavily-shaded hand.

Xanadu

This work was not identified on any other documentation of the tomb that I was able to find. But looking through the 1925 monograph I found this mysterious design that matches the sculpture. This is an imagined view of Kubla Khan summer palace and the city of Xanadu. While clearly fantastical, it reveals many shared compositional techniques and the adept hand in adapting historical styles exhibited by Goodhue's built works.

Many of his fantasies share this tiered / terraced composition, something he was never able to fully realize in his built works. The Baltimore Cathedral would have been that realization. But it does appear to a lesser degree in most of his larger buildings.

The inclusion of this design among his built works shows that the frieze is not intended to represent just his constructed achievements, but his design thinking more holistically. It also highlights his individual personality in addition to his partnerships, collaborations, and the work of the studio he led.

Rockefeller Chapel, University of Chicago

A strong tower dominates the design of the University of Chicago's Rockefeller Memorial Chapel. Goodhue began the design in 1918, but construction did not begin until after his death. The design carved into the tomb is based on an earlier rendering and does not match the final design of the chapel.

The University's Rockefeller Memorial Chapel website has excellent information on the art and architecture of the building including some detailed descriptions of the sculptural components.

The chapel incorporates collaborations with craftspeople: stone sculpture by Lee Lawrie and Ulric Ellerhusen, mosaics by Hildreth Meière, and woodcarvings by Alois Lang. While the exterior architectural massing and all of the interior components are well executed, the integration is not as successful as Goodhue's other churches. Compared to these others, there is a vagueness to the interior that may be related to the breadth of the chapel's purposes, the relative lack of spiritual specificity in its program, and to the larger scale that dilutes the ornament and separates it from the building fabric.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pallrokk/albums/72157650442894864

The University of Chicago's coat of arms identify this building on the frieze.

Nebraska State Capitol, Lincoln, NE

Goodhue's largest and most high-profile work occupies the center of the frieze set apart by from the other by considerable negative space. This is the Nebraska State Capitol, built between 1922 and 1932. As with the other projects discussed here, the capitol building features integrated works of art in a strong Deco Americana. Lawrie and Meière feature heavily.

The coat of arms appears to be a unique construction simplifying elements from the State Seal of Nebraska.

Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University

The Sterling Memorial Library, completed in 1930, shows the greatest difference from the drawing used for the frieze to the final version. Following Goodhue's death, James Gamble Rogers completed the design in a more overtly historicist Collegiate Gothic.

To the right of the library building Lawrie carved an open book with the Hebrew words "Urim v’Thummim," the centerpiece of the seal of Yale University. Below the library is the Latin equivalent, "Lux et Veritas."

Los Angeles Central Library, Los Angeles, CA

The Central Library of the Los Angeles Public Library opened in 1926, two years after Goodhue's death. It is one of Goodhue's most idiosyncratic works and shows his ability to build on revival styles in an original yet cohesive form. With St Bartholomew and the Sterling Library, it gives some indication of the direction Goodhue and his firm might have taken among the architectural changes that characterized the next few decades had his life not been cut short.

The escutcheon with this building is the same as that on the building's cornerstone. It incorporates rearranged elements from the Seal of the City of Los Angeles: the eagle and shield from the Seal of the United States (in place of just the shield), the eagle and serpent from the coat of arms of Mexico, and the castle from the coat of arms of Castile. (I have not yet been able to confirm if the shield in this arrangement was used by the city or the library of Los Angeles at any point or if this is a unique creation of the architects and artists.)

St Thomas, Manhattan

This was the last major work designed in collaboration between Cram and Goodhue and among the most high profile. Tensions over the design contributed to the split already between Cram's Boston office and Goodhue's New York office. Construction of the 5th Avenue church occurred between 1911 and 1914 and dedicated in 1916.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pallrokk/albums/72157659364830938

The contrast between the image of St Thomas here (which is a photo as the 1925 monograph does not include an exterior elevation drawing) and the façades of Goodhue's other churches of similar scale also reflects a distinction between Cram's more urbane pointed Gothic than the more picturesque Anglo-catholic Gothic blended with earlier ecclesial styles used by Goodhue.

Among the elements that seem to me to reflect Goodhue's influence include the relief of St Michael on the World War I Memorial (also sculpted by Lee Lawrie):

and the Chantry Chapel:

The altar and sanctuary of the Chantry Chapel in particular such as inlaid stonework, patterned tilework, and integrated text.

The shield identifying this church on the frieze shows a builder's square, one of the attributes of St Thomas reflecting his traditional profession.

California State Building, Panama-California Exposition, San Diego, CA

The Panama-California Exposition opened in 1915 in San Diego. Bertram Goodhue served as the primary architect for the entire exposition which he executed in a Spanish Baroque (or Spanish Colonial or Mission Revival) expression over a regional and stylistically appropriate adaptation of the Beaux-Arts plan typical of the great expositions of the late 19th and early 2oth century.

The California State Building was the event's signature building with its large dome and tower dominating the main entrance to the park (the West or City Gate) over the Cabrillo Bridge. These four elements represent the exposition on the tomb frieze, and all four remain standing as part of the anthropological Museum of Man in Balboa Park, downtown San Diego.

The scallop shell is most likely a reference to the Spanish colonial Province of the Californias that is still used by the Mexican state of Baja California Sur. It does not appear as an emblem of the exposition on any of the print materials I have been able to review, so its selection may have been the artists' own. Like the NAS lynx which may was taken from the ornament used on the building, the the scallop shell may be a reference to its use on the buildings and its frequent use as an ornamental form in Spanish Baroque architecture and frequently used on the Spanish missions in California.

St Vincent Ferrer, Manhattan

Consecrated in 1918, St Vincent Ferrer represents Goodhue's most richly developed Gothic church. The luminously dark interior is the perfect example of the prevailing image of Victorian Gothic. Here the stonework—framing very French jeweled windows—is itself the dominant ornament. Small but precise sculpted elements adorn the interior.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pallrokk/albums/72157659771185295

With St Vincent Ferrer, Lawrie carved a shield with the cross fleury, the central component of the coat of arms of the Dominican Order.

St Bartholomew, Manhattan

I wrote a long appreciation of St Bartholomew on this blog not too long ago. It is truly one of the finest examples of church architecture of all time.

In order to match the the carving, the image on the left is actually a composite of the photograph included in the 1925 monograph and the drawing of Goodhue's design for the crossing tower. The design was incomplete at the time of Goodhue's death and was modified by his firm for construction, but it was Goodhue's version that Lawrie depicted on the frieze. The final tower design may not have been completed at the of the tomb's installation as the church was not completed until 1930.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/pallrokk/albums/72157631762138757

The coat of arms with St Bartholomew is one of the saint's traditional attributes. Each of the apostles can be represented by the instrument of their martyrdom (or attempted martyrdom, in the case of St John). For St Bartholomew, this instrument is the knife with which he was flayed before his crucifixion.

At the time of his death, Bertram Goodhue was at the height of professional esteem and popularity. His unusually dramatic (for an architect) tomb reflects this status. The tumultuous architectural environment of the remainder of the 20th century may have diminished the appraisal of his status in the profession and relegated him to the category of embarrassingly historicist. Such an assessment grossly obscures his immense skill, the malleability with which he treated the revival styles in which he worked, and the contributions he made to building-integrated modern figural art. But at his passing, Lee Lawrie and many other of Goodhue's friends and contemporaries created an eminently fitting monument to the architect drawing on characteristics of his own design work and the English high-church traditions that inspire his own architecture.